Fitter, Happier… The Rise Of Social Robots

PhD student Katie Winkle explains how socially assistive robots can provide motivation and guidance for those in need of a companion.

On 4 August this year, the maverick French inventor Franky Zapata crossed the Channel on a jet-powered hoverboard, with the 21-mile journey taking him just over 23 minutes. Clearly a remarkable achievement, but also a very public prompt to all those working in labs on the cool tech of the future – as envisioned by the sci-fi shows of the 50s – that they need to up their game. Yes, the white-coated technicians responsible for jetpacks, flying cars and robot housekeepers – we are talking about you. Teasing aside, Katie Winkle, a PhD student currently undertaking research at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, specialises in the field of Socially Assistive Robotics (SAR) and is certain that her area of study isn’t an unrealisable sci-fi pipe dream.

“I don’t think the use of robots as social companions and helpers is that far away, actually,” she says confidently. “Right now, I could program a robot for a specific use case for a school or a hospital. The real difficulty is in scaling that up in a way that still works for lots of different people and applications. That’s why we are researching it, but it is doable. I’m optimistic.”

Want to study Robotics?

Socially Assistive Robotics is a relatively new area of robotics that focuses on assisting users through social rather than physical interaction. So while there are physical robots that have been designed to help with ostensibly manual tasks as varied as assembling cars or even picking strawberries, a Socially Assistive Robot is subtler than that.

They’re not going to help you out of bed by lifting you, but they might tell you to get out of bed. Or they might remind you to take your medicine.

They can support a trained practitioner, such as a teacher, to provide guidance and motivation to a person – in doing so, they attempt to give the correct cognitive cues to encourage development, learning, or therapy.

As Katie explains: “The distinction is that these robots aren’t physical, they are social. They’re not going to help you out of bed by lifting you, but they might tell you to get out of bed. Or they might remind you to take your medicine. They could even help to combat the issue of loneliness. The key is that the usefulness comes from the social interaction, such as conversation and companionship, rather than a physical act.”

Pet rescue

Another key definition is that a Socially Assistive Robot is not simply for entertainment and they should perform a useful process. But what are the main fields that these robotic companions could help and what are the tangible examples?

Robots have been introduced into nursing homes, where dementia patients have been given robotic pets to help with wellbeing. There’s certainly less mess than with a real dog.

“There are many, but the two areas I always mention first are health and education,” says Katie. “The applications we are starting to see linked to mental health are generally based around loneliness and dementia care. Robots have been introduced into nursing homes, where dementia patients have been given robotic pets to help with wellbeing. There’s certainly less mess than with a real dog.”

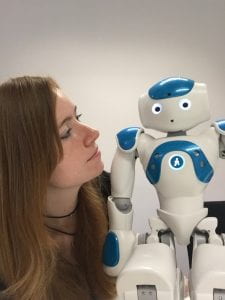

Another example is the use of robots in autism therapy. For children who have autism or social anxiety, robots can provide a safe social companion, ‘someone’ they can practice social interaction with. Autistic children respond well in these circumstances. In these cases, the robots are being essentially used to help them with their social skills and that has a very real application of putting them back into human-human interaction.

“All these robots are helping where you need a social presence and there isn’t a human available,” explains Katie. “So, in between therapy visits or gym sessions, there is a robot there to provide the motivation you don’t have.

“As a proposal for future research here at the Lab, I would love to take a robot into Bristol Childrens’ Hospital and use it as a companion for children who are isolated there long-term.”

The use of Socially Assistive Robots in education is essentially the same thing again: helping children who perhaps need extra attention, or children in group sizes that are too big. The robot can perform small group work.

“It’s anywhere where you’d like to have an intelligent social presence, but you don’t. They are all cases where social influence is important,” adds Katie.

Personality issues

It’s important to Katie that her work at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory must at all times consider the end-user, the human who is being assisted by the robot. Just as you might not get along with your teacher or clash with the personality of another, is there any guarantee you’ll get on with your robot?

“The personality type of the robot needs to suit the personality of the person it is helping.”

“When we talk about robot personalities and robot emotions,” explains Katie, “what we are really saying is how well can we program a robot to look like it has those. This means we need to learn about human behaviour and then hook it into a robot. If someone is an extrovert, they’ll talk a lot, move hands about… we can model many of those things from psychology and put it on a robot. The personality type of the robot needs to suit the personality of the person it is helping.”

Metal motivators

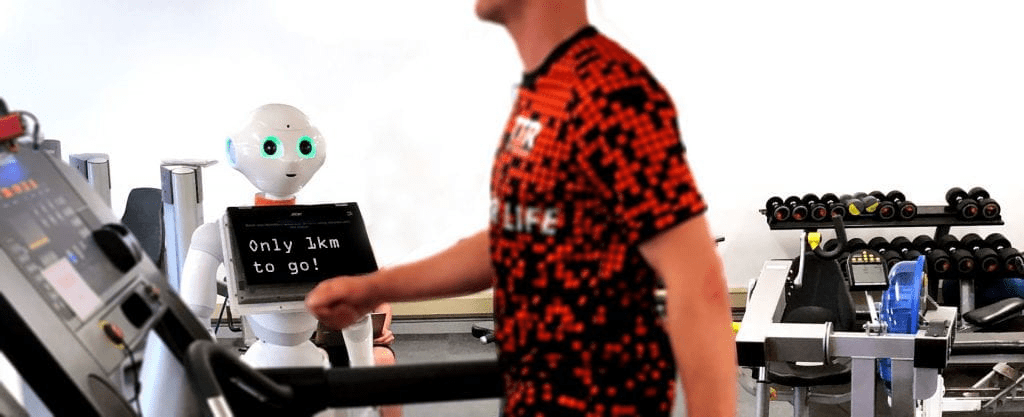

“I’m working on a study right now where I’ve got a robot set up in the gym over on campus. The idea is to help people with the Couch To 5k running programme over a nine-week programme, with the robot assisting three times a week. To begin with, the robot is being controlled with the fitness instructor and over time, the robot will learn how to give encouragements at the right time.

“The robot will be giving the runners challenges. Some will respond to direct encouragement – ‘Come on, you can do it! Push a bit harder!’, while with others, it will be more sympathetic, because that’s what they need. Personalisation of robot interaction is a big thing.”

Katie’s Couch To 5k study is an easy-to-understand, tangible concept that brings the near-endless possibilities of Socially Assistive Robots to life. But are there any areas where they won’t be able to help?

We’ll leave the final word to Katie: “I’ve seen work investigating the effectiveness of a ‘marriage counsellor’ robot – it was a talking head in a wig that was supposed to facilitate conversation in couples therapy. Even I’m not sure about that one just yet, it’s a bit of a stretch.”

Academic profile

Name: Katie Winkle (MEng)

Title: PhD Student at Bristol Robotics Laboratory

Studies:

MEng Mechanical Engineering

PhD Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Katie’s story:

“Growing up, I was interested in cars, in how machines work, stuff we can build using science in an applied way. My dad was a car mechanic and he encouraged my curiosity.

“My Undergraduate Degree was Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bristol. I was all set to go into the automotive industry and wasn’t at all thinking about robotics. Then we had a final-year lecturing unit on the subject and it completely captured my imagination.

“I originally thought I’d work with very physical assistive robots, like those that help you walk. But as I got here, I found I was much more drawn to social interaction. I found it much more interesting. I was amazed that I could put a social robot in front of somebody right now and how I could make that useful. I find the underlying psychology so fascinating and that’s why I’m where I ended up now.”