Can Drones Learn From Nature?

PhD student Cara Williamson tells us how studying gulls flying around Bristol is helping her programme more efficient flight paths for drones.

Unmanned aerial vehicles, drones, are rarely out of the headlines. The world’s first driverless passenger drone has already been tested in China, and major companies have begun trialling drone deliveries to customers.

But despite this huge acceleration in popularity there’s a number of challenges which drone manufacturers are facing, not least the matter of urban drone navigation. To investigate this problem, PhD students Cara Williamson and Anouk Spelt are studying urban gulls to understand the most efficient flight paths through urban landscapes. We spoke to Cara to learn more about their project.

Drones could benefit society in so many ways, from the obvious, such as parcel delivery, to the life-changing, such as being the first point of contact for emergency services.

“The Urban Gull Project was started in 2016 by myself and Anouk Spelt as part of our PhD research. We’re supervised by Dr Shane Windsor who won a grant to start the Bio-Inspired Flight Lab. Over millions of years, nature has optimised for every environment – urban gulls are particularly adept at coping with the complex wind flows around city buildings. UAVs could use similar flight strategies. Drones could benefit society in so many ways, from the obvious, such as parcel delivery, to the life-changing, such as being the first point of contact for emergency services.

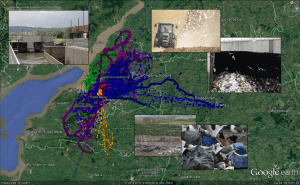

“The project brings together biology and engineering, using GPS devices on 11 lesser black-backed gulls in Bristol. The tiny backpacks (under 3% of the bird’s weight) track location, altitude, speed and 3D acceleration data which tells us whether the birds are soaring or flapping. Preliminary research showed how gulls position themselves in updrafts on the windward side of buildings to improve control and mitigate risks from gusts. These wind-highways help them maintain altitude so they can soar for a third of their flight time. We’re now seeing that gulls choose routes to foraging grounds that save them energy, even if they are twice the shortest distance.

Battery life is a big problem for drones. Batteries are heavy and limit their range and endurance.

“The wind modelling and path planning method I’ve been using is very quick and could be run in advance of a UAV making a delivery, for example, in order to pick a route that keeps energy costs to a minimum. Battery life is a big problem for drones. Batteries are heavy and limit their range and endurance.

“We collect habitat and weather data in and around Bristol. It’s the perfect location as it combines a diverse built environment with an established gull population. Over the last few decades, the birds’ distribution has moved away from traditional seaside haunts. It’s thought that cities offer warmer temperatures, protected nesting sites and rich pickings from our litter. Anouk compares the gulls’ foraging behaviour and energetic costs with their rural cousins to establish what is really going on. Despite being referred to as seagulls, our birds don’t visit the sea at all during breeding season (March-August), which is why we use the term urban gulls (first coined by our collaborator and South West gull expert of over 30 years, Pete Rock).

“Having followed the gulls for three years, we’ve seen a gull laying an egg, held hatching eggs and watched chicks taking their first flight. Our work has taken us to the top of landfills, quarries, the waste treatment centre and up many tall buildings and church spires. The gulls have distinct traits – we even named some of them after our favourite Game of Thrones characters; Arya (quite feisty – tried to peck us); Sansa (the most beautiful); Lady Brienne (the largest) and Tyrion (the smallest). We also got very attached to the first season’s chicks and learnt the hard way that nature can be quite brutal. It would be good to mend the human-gull relationship. We want to get the message out that when animals thrive in the environments we create, they can teach us so much. It’s vital to study and conserve the natural world.

“At the moment, we’ve got a packed programme of workshops in schools. Pupils design and fly drones and find out about bio-inspired engineering and wind pattern modelling. We’ve had some really encouraging feedback and we hope we’ve inspired a new generation of kids to take STEM subjects that they wouldn’t have previously considered. We were really pleased that this outreach programme was recognised when the project was shortlisted for the 2018 Airbus Diversity Awards.”